For most electronics products, the BoM accounts for 20 - 60% of total manufacturing cost, so teams invest enormous energy trying to reduce it.

But here’s the truth:

By the time most organizations start optimizing the BoM, 70 - 90% of the cost has already been locked in by upstream design decisions.

Procurement and engineering can still capture incremental savings, but the structural cost of the system is determined much earlier – when architecture, key ICs, and component choices are first made.

Where Traditional BoM Cost Reduction Falls Short

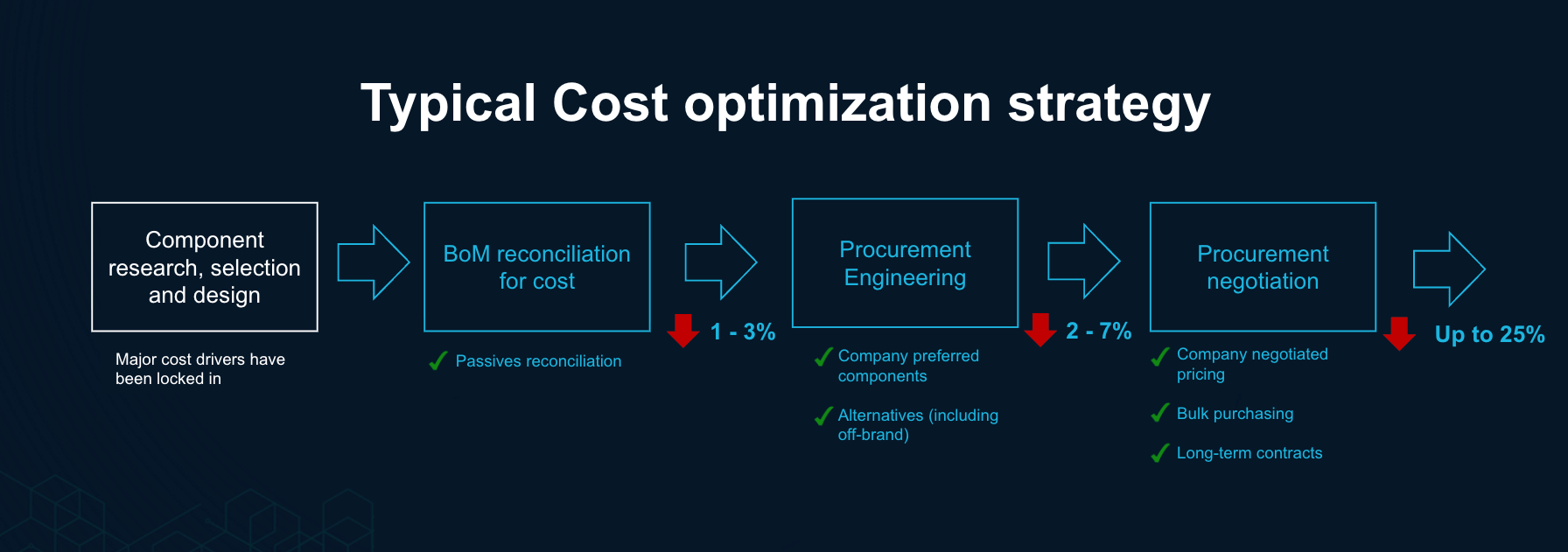

Once a design is mature, the available cost-reduction levers narrow to three categories – all downstream from the decisions that structurally define system cost.

1. Reconciliation and housekeeping (1 - 3%)

Teams collapse passive values, replace over-specified parts, and reduce supplier sprawl.

Useful work, but it almost never touches the components that drive meaningful BoM cost.

2. Procurement engineering substitutions (2 - 7%)

Footprint-compatible drop-ins, package migrations, and alternate sourcing can move the needle, but at this stage:

- thermal margins are already fixed

- firmware is tightly coupled to silicon

- PCB constraints leave little room for change

This is why late substitutions so often lead to respins, signal-integrity surprises, thermal violations, or firmware rework – even when the parts look “compatible” on paper.

3. Procurement negotiation (up to 25% on certain items)

Bulk purchasing, multi-SKU aggregation, and long-term contracts can meaningfully reduce cost – but only on parts where pricing is negotiable.

For microcontrollers, radios, memory, and other architecture-defining components, pricing is typically rigid or sole-source.

While these levers absolutely matter, they come in play after the architecture and component choices that determine the system’s cost structure. They’re tactical corrections, not strategic cost control.

Why Upstream Cost Optimization Rarely Happens

Upstream cost control means evaluating architecture and components before the design is committed. In theory, this is where the biggest savings lie – but in practice, optimization here is “best-effort” or simply never happens. Three realities get in the way.

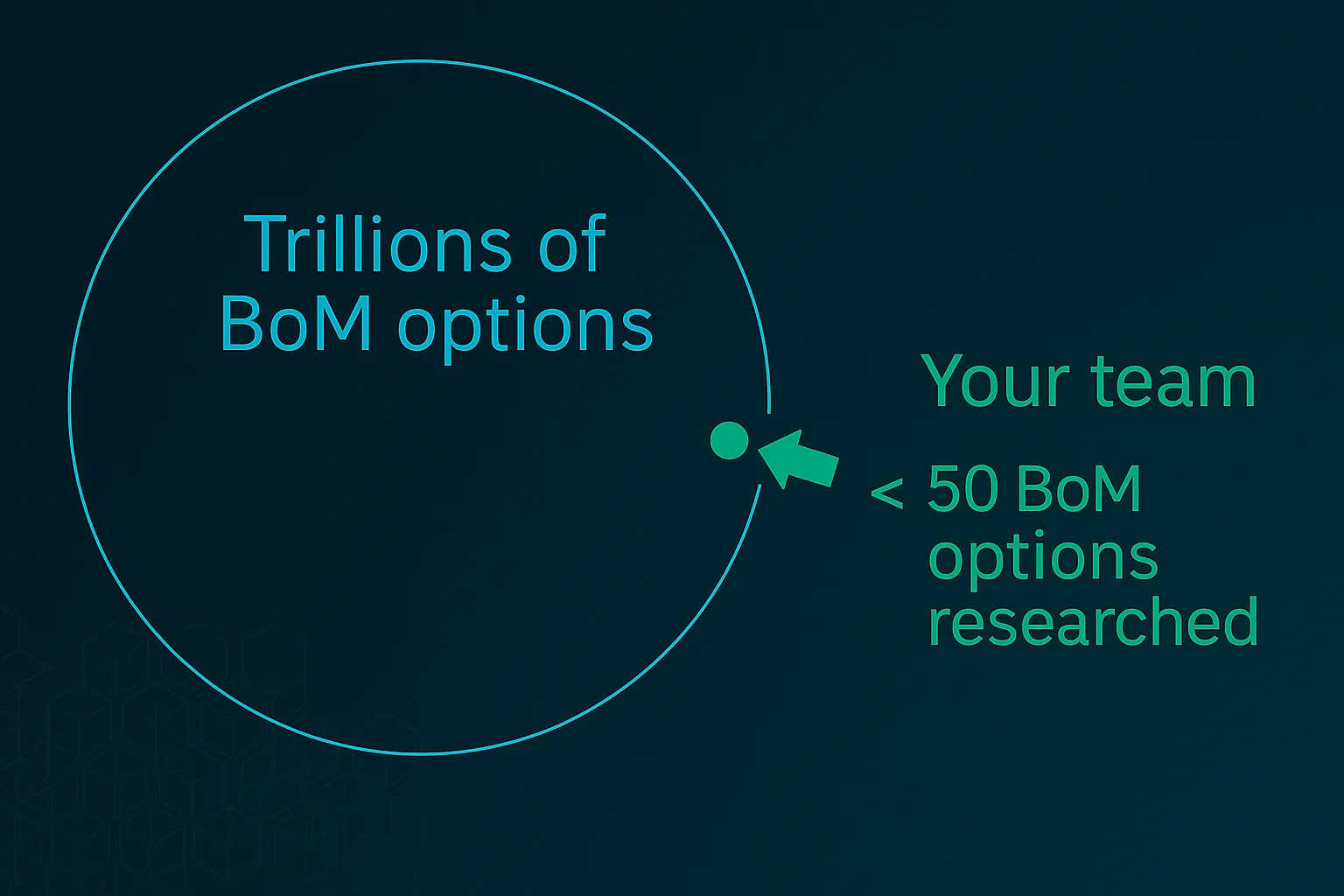

1. The design space is too large for manual exploration

Online component databases contain 20 - 40 million parts. Even your company-preferred components likely span tens of thousands – each with dozens or hundreds of parameters. Combine permutations across even a modest board and you get billions of possible configurations.

In reality, most engineering teams evaluate fewer than 50 BoM options before committing.

That shallow search leaves 99.99% of viable design paths unexplored – a dynamic we examined in greater depth in Unturned Stones: How Manual Electronics Design Leaves Innovation Buried.

2. The anchor components are chosen early, and that limits the potential for BoM cost optimization

MCUs, radios, and memory, often representing 10 - 30% of total BoM cost, are selected early, when the architecture is being defined.

Once chosen, they narrow the system’s performance, power, thermal, mechanical, firmware, and compliance profiles. Changing them later is rarely feasible.

Why Early Selections Lock the Architecture

3. Manual workflows bias teams toward “safe” choices

Compressed schedules push teams to reuse familiar components – even when better, cheaper, or more available options exist.

This “design inertia” locks cost and supply risk into products for years.

The biggest savings remain hidden upstream because manual workflows simply can’t explore the design space or revisit architecture-defining choices once teams are under pressure to ship.

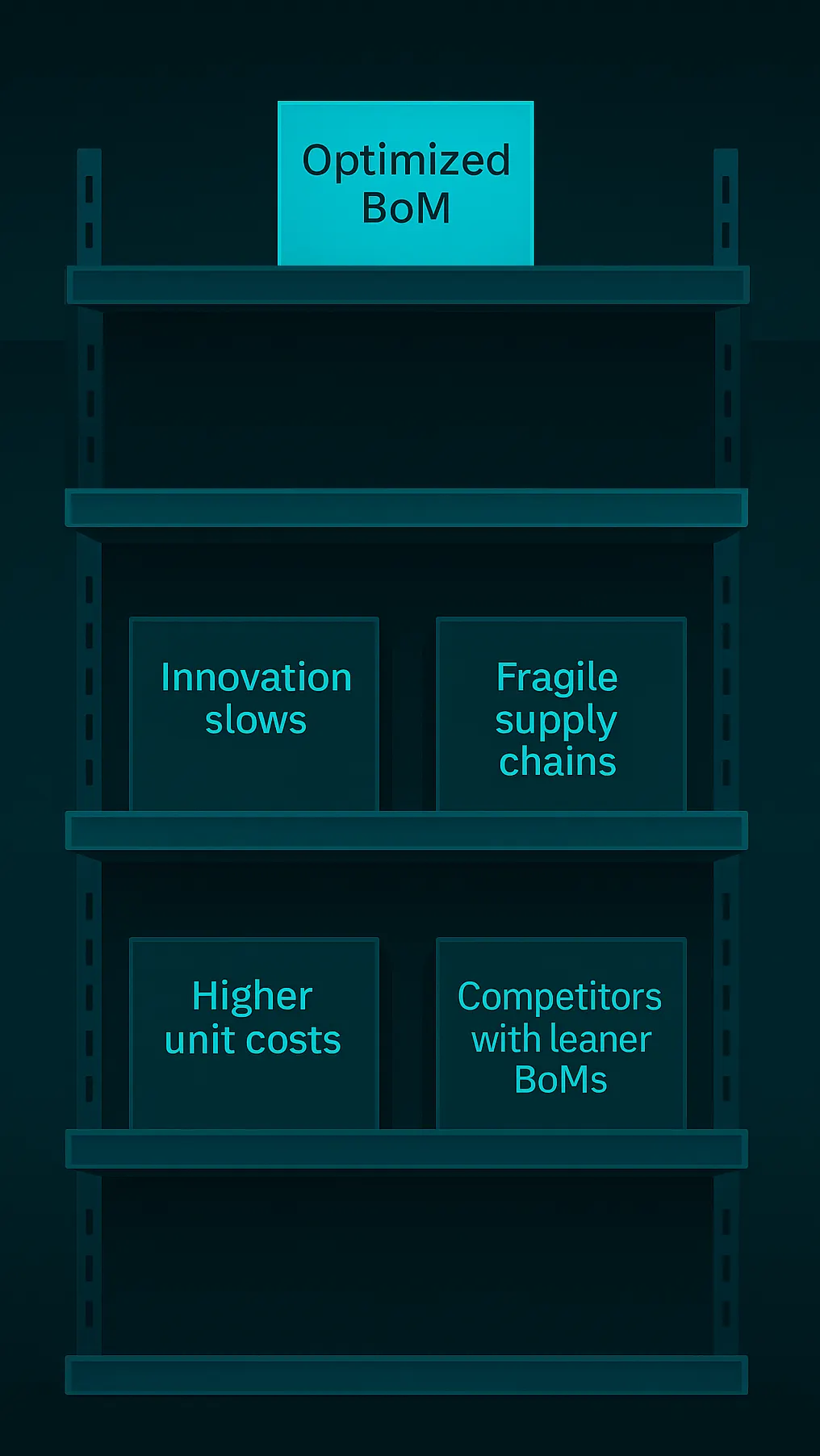

The Cost of “Best Effort” Design Exploration

When upstream optimization is out of reach, the consequences surface months later – during integration, validation, procurement, and production. These problems appear downstream, but their root cause is almost always early architectural lock-in.

The downstream impacts of shallow design-space exploration

When early design decisions are made with limited exploration, downstream teams inherit cost, risk, and fragility that compound over the product lifecycle.

These issues don’t affect a single PCB – they shape the economics and resilience of entire product lines.

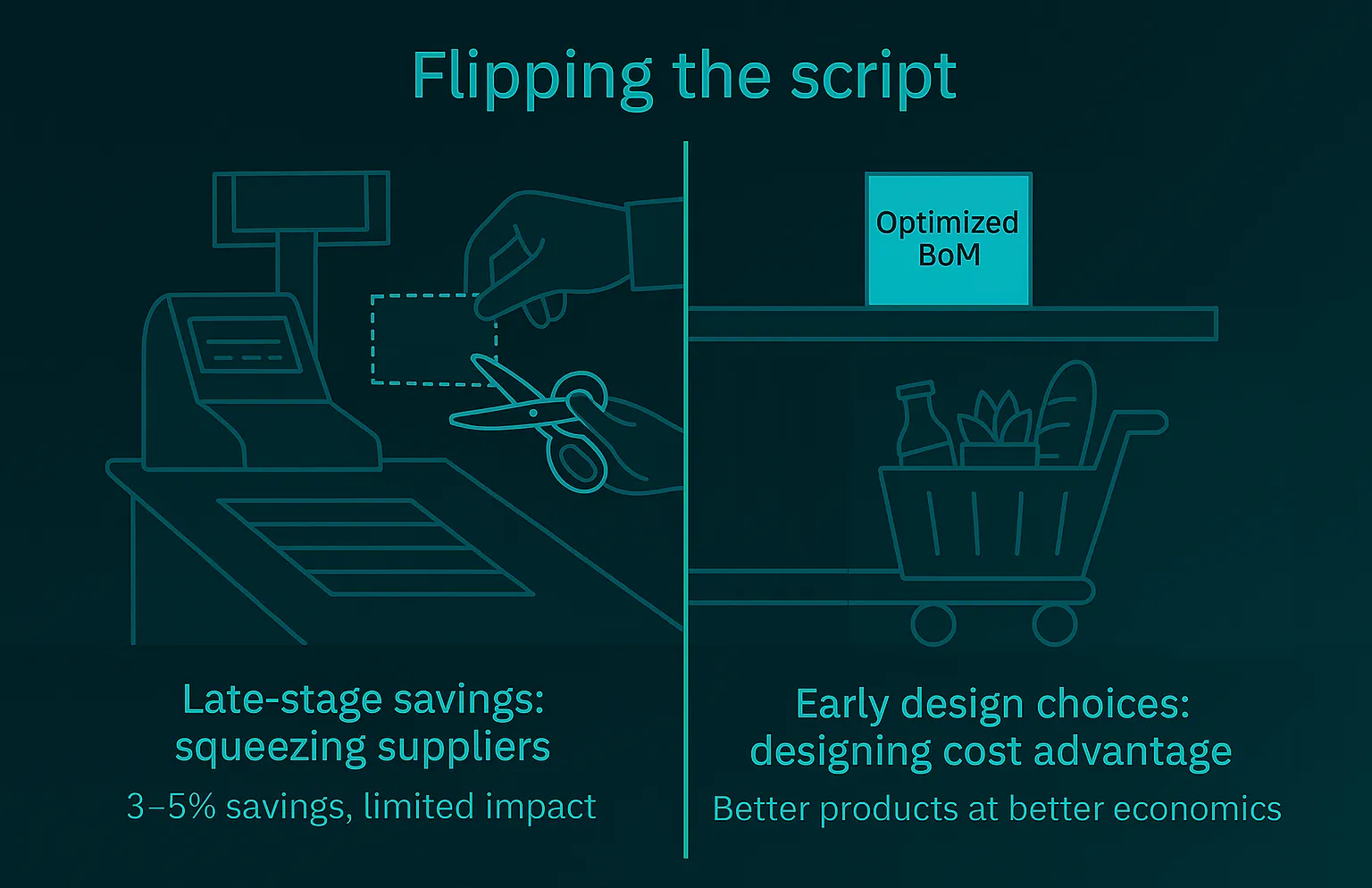

Cost as a Design Variable, Not a Late-Stage Adjustment

Treating cost as a first-class design constraint is not about compromising performance, it’s about optimizing the entire system holistically, at a point when the major tradeoffs are still flexible.

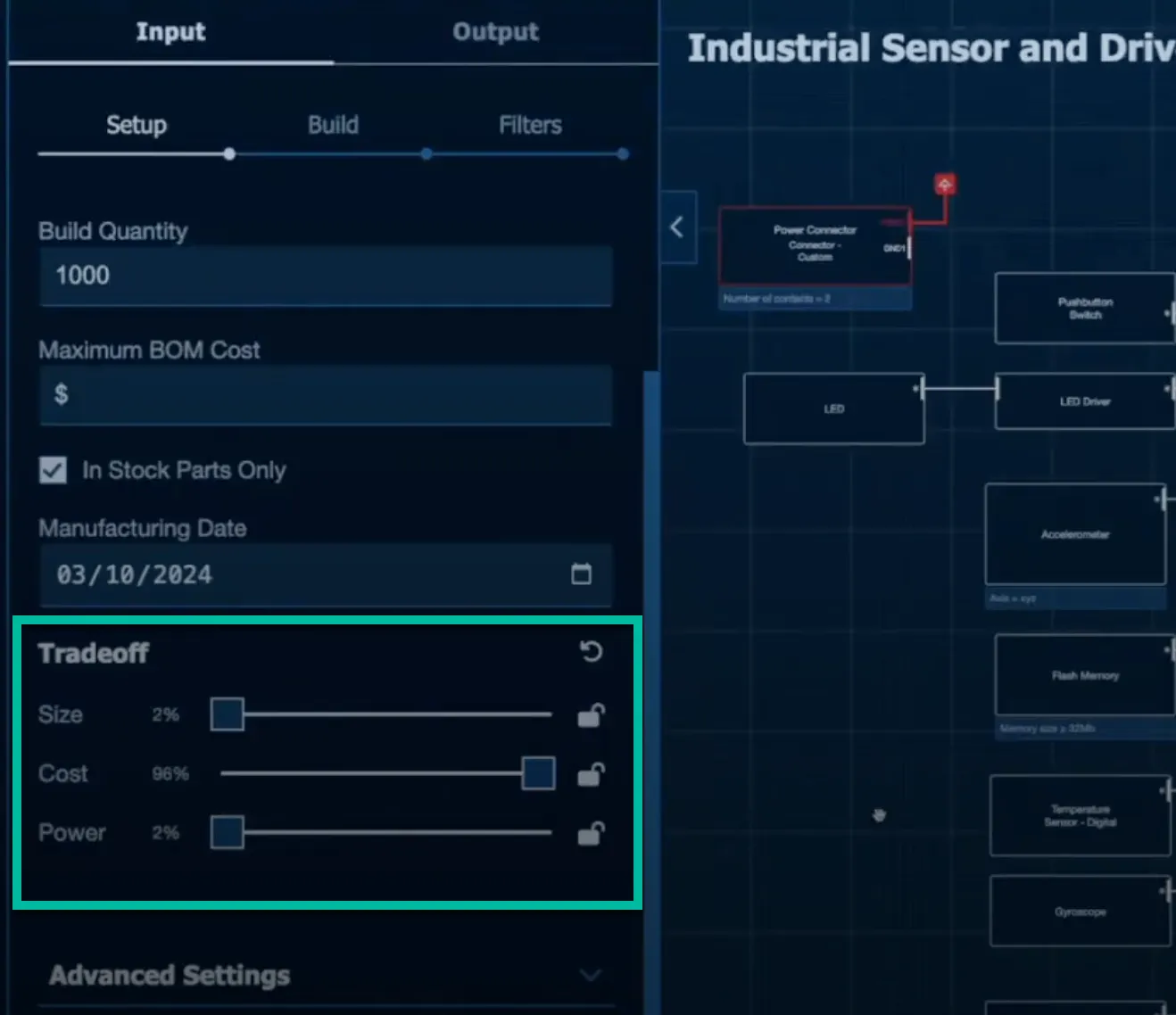

In practice, this means engineering teams evaluate cost, performance, power, availability, and reliability as a single design problem, instead of isolated conversations scattered across weeks or months.

When cost is a key architectural objective it’s no longer just “optimization at the edges.”

AI-Powered Design Exploration: A Practical Path to True Upstream BoM Optimization

Upstream BoM optimization has always been the highest-leverage point in the design process, but until recently, it was impractical. AI and advanced engineering algorithms remove this limitation.

Instead of evaluating a few dozen configurations, engineering teams can now explore thousands to trillions of design paths, assessing cost, performance, power, availability, and reliability in parallel.

This unlocks decisions that were previously inaccessible:

- lower cost and higher reliability

- better performance and stronger supply assurance

- smaller footprint and reduced power

- more design headroom and fewer downstream risks

AI doesn’t negotiate harder – it exposes architecturally superior design options that manual processes never surface.

A real-world example:

Their engineers automatically generated multiple validated BoMs, compared tradeoffs, and selected the optimal architecture for cost without sacrificing critical requirements.

Designing Cost Advantage Into the Architecture

When engineering teams consider cost upstream – alongside performance, power, availability, and reliability – they gain control over outcomes that no amount of downstream optimization can replicate.

Instead of chasing savings at the end, they design for:

- More resilient supply chains through better component and architecture choices

- Lower lifetime cost of ownership for both the product and the engineering organization

- Improved thermal and power behavior through smarter system-level tradeoffs

- Fewer respins because key constraints are handled upfront

- More predictable schedules with fewer late-stage surprises

- Higher product margins baked into the architecture itself

With AI-driven BoM exploration, the fundamental question shifts:

From: “Where can we save money now that the design is done?”

To: “What is the best possible design the market, technology, and supply chain can support?”

This reframes cost as a strategic design dimension – something engineered into the system, not negotiated after the fact.

At Circuit Mind, our AI-powered automation makes this level of upstream exploration practical, enabling teams to create designs that are lower-cost, more resilient, and first-time-right.

If you’d like to see what’s hidden in your current design space, we’d be glad to walk you through it. Book a time with us →

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)